Telegram is a popular messaging service that aims to provide privacy and security, but it has its own issues.

Instant messaging, in its current state, is a bit messy. A lot of people are using (and often juggling between) different centralized services and apps to communicate with family, friends, coworkers, and other associates; some examples of instant messengers include Facebook Messenger, Android Messages, Skype, and even iMessage. While having a multitude of services isn't inherently bad in and of itself, it presents some issues: data between users is stored and collected onto servers owned by the service provider, which may lead to privacy and backdoor issues such as targeted advertising; third parties use your data for unintended uses, and even tracking from parties or governments.

These services also aren't able to communicate between each other as easily, making it difficult to move from service to another. Simply stated, there isn't a viable standard for instant messaging that benefits everyone. How ever, the developers at the Matrix Foundation have been working diligently to solve this issue by creating a new, open, and decentralized standard for instant messaging communications called Matrix, which also provides the ability to bridge between services. Through Matrix's technical capabilities and France's adoption of the protocol as their standard for instant messaging between government departments and to the French public, Matrix will play an important role in the future as the primary standard messaging protocol.

Decentralized messaging as a whole

In order to really understand what Matrix is and how it works, it is important to understand the basic principles of decentralized instant messaging in general. In "A Distributed Instant Messaging System Model" from the Metallurgical and Mining Industry journal, Hao Zhang, Zhongkui Sun, and He Li describe the properties of this model of instant messaging. First, the authors state that decentralized messaging, at least for two people, will work similarly to regular networks in the sense that data will be sent to the same location (Zhang, Sun, and Li 489). While this point doesn't necessarily paint the entire picture of how decentralized messaging works, it does help establish the fact that, at decentralized messaging’s core, it still remains an easy-to-use system for communicating. When more people join, the only thing that changes is that, instead of one server, there are several that help distribute data.

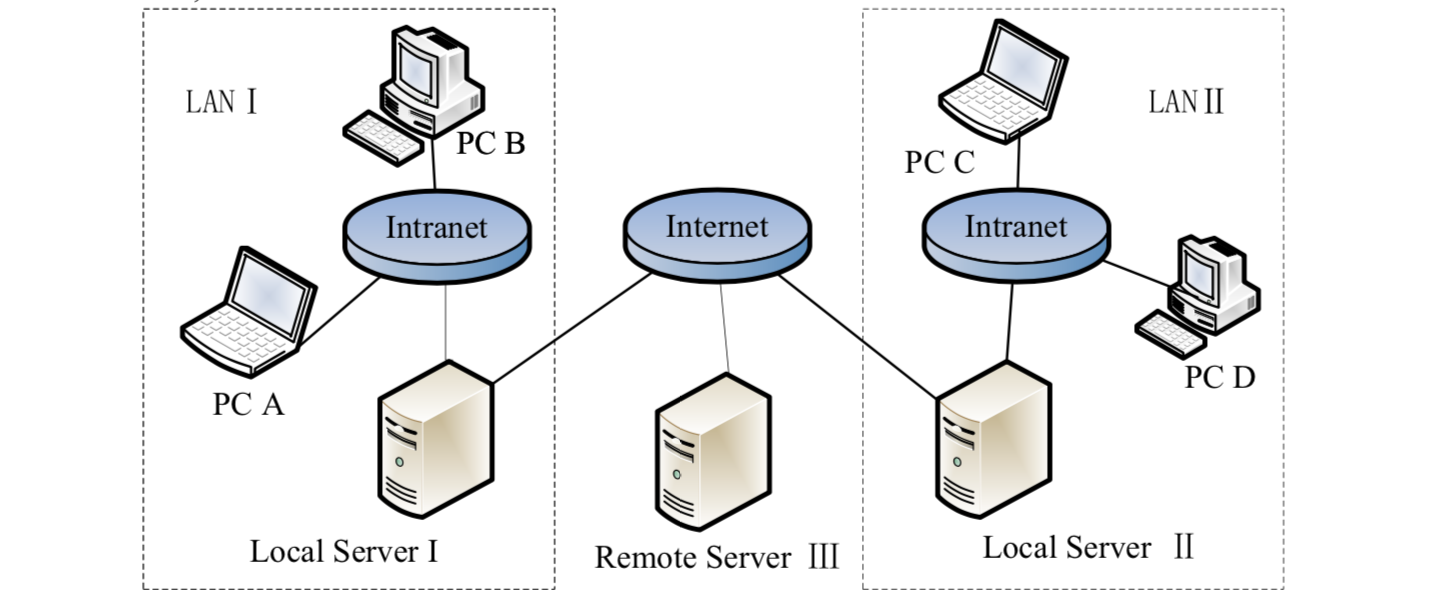

This diagram from "A Distributed Instant Messaging System Model" helps demonstrate what a distributed model looks like (Zhang, Sun, and Li 491).

Second, because having multiple servers distribute data makes transmissions easier, Zhang, Sun, and Li also state that statuses of when people are online and offline are sent to all other networks and computers (Zhang, Sun, and Li 489). This distribution of data and statuses in this manner helps ensure that the messaging network remains online at all times. If a server in this network goes down, all other computers and networks will still retain the status updates, meaning that users will always know when someone is online or offline, and they will know this much more quickly. If a user was waiting for this kind of notification on a centralized server when that service went down, they'd never know because the data wouldn't get transmitted. Although this point strictly applies to offline/online statuses, this structure is also applicable to many other forms of data, such as member counts, files uploaded, time stamps, and typing indicators.

Besides the core idea of using multiple servers, Zhang, Sun, and Li remark that data, in a distributed messaging system, is sent with a common structure that other computers can read (Zhang, Sun, and Li 491). When data is transmitted between networks, it needs to be readable to other computers that are receiving this data; therefore, there must be a common protocol (procedure or system of rules) in place that dictates how this data is read. This structure is important, especially if users are on different services; this common protocol would let any user from these services to receive and view the data exactly as it was sent, albeit with some user interface changes. The data could range from typing indicators to images or videos.

Finally, if two users are on completely different services where the two cannot communicate directly, the authors propose that data can be sent through a Web service, typically from another server elsewhere (Zhang, Sun, and Li 491). A Web service, in this context, refers to a service on the Internet that data is sent to and then sends to another location. For decentralized messaging, this means that if two computers can't connect to each other in the same network, they can use the service to exchange data more easily. If both users can't connect to each other directly in that network, they can still send and receive messages, though the transmitted data will go to another location first before reaching its destination. In the aforementioned case of users on different services, this can be extremely helpful, as some Web services will also translate data to a format the service can read. For instance, if Alice and Bob were messaging each other, but Alice is using Platform X and Bob is using Platform Pro, the Web service would be able to translate Platform X messages into Platform Pro ones and vice versa, meaning that Alice and Bob can still talk to each other without difficulty.

Matrix as a decentralized service

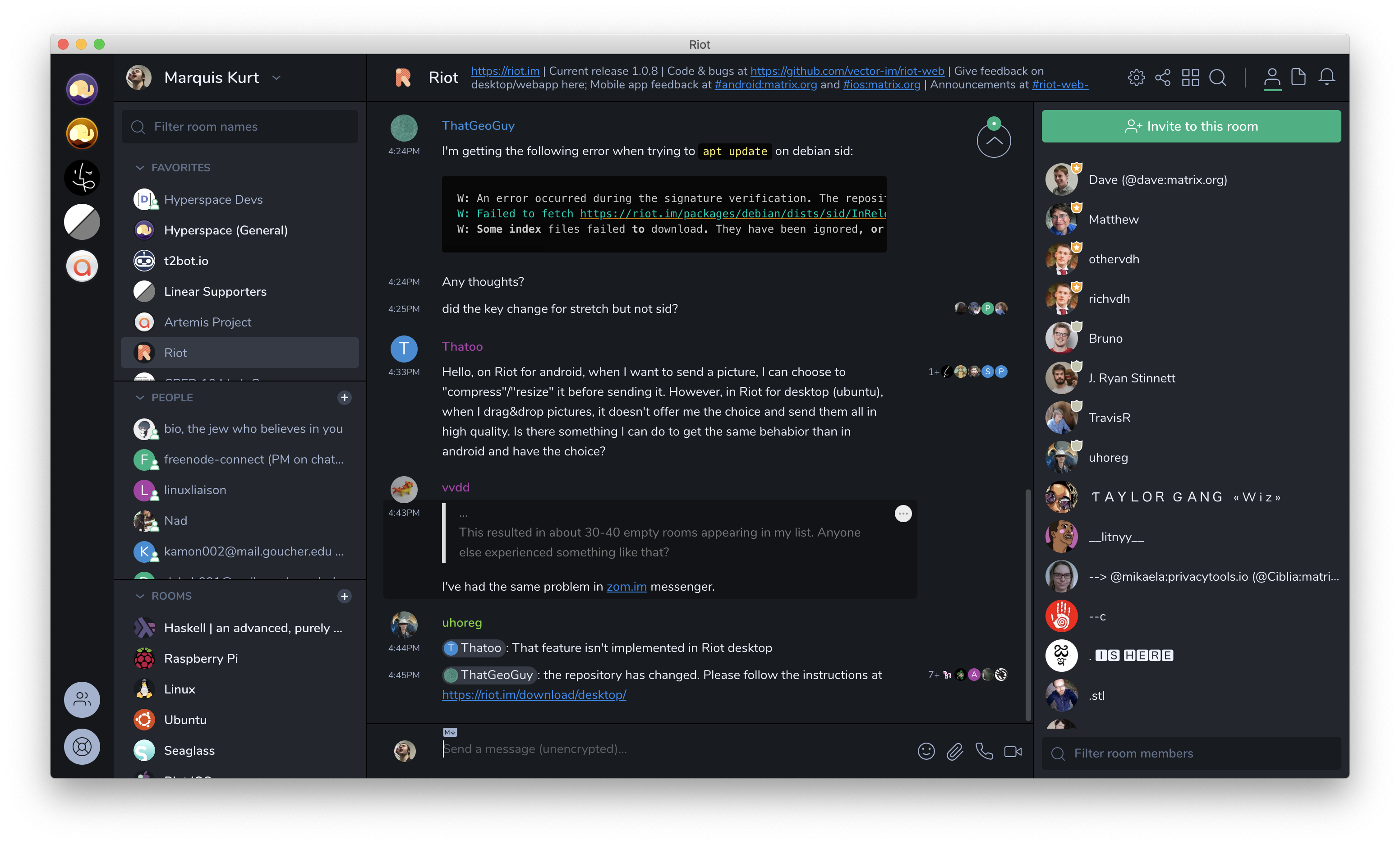

Riot.im is a usable and glossy frontend for Matrix, though other options such as Seaglass and Spectral exist.

Given that a decentralized messaging system adopts all of the standards that Zhang, Sun, and Li have defined, Matrix can be easily classified as a decentralized messaging system thanks to its technical capabilities. According to the official specification, Matrix is "a set of open APIs for open-federated Instant Messaging[... that provides] an open decentralized pubsub layer for [...] publishing/subscribing JSON objects" (Matrix.org 2018, "Introduction to Matrix APIs"). The introduction of the specification has defined Matrix as the common protocol for transmitting data between computers. Most importantly, the developers of the protocol have defined a very common data format to be the basis of the protocol, JSON (JavaScript Object Notation), which is commonly used on the internet to get and post data. Because of how frequent JSON is across the Internet, Matrix is becoming an easily-adoptable protocol that uses open Web standards.

Similar to what Zhang, Sun, and Li propose, Matrix distributes its offline/online statuses to other computers and servers (called "homeservers" in Matrix). In the "Room structure" section of the specification, Matrix shares this data across networks at different levels: "Federation maintains shared data structures per-room between multiple homeservers” (Matrix.org 2018, ”Room structure"). Each chat is located in a room, and homeservers contain a group of rooms. Matrix distributes offline/online states to both the rooms themselves and the whole network. However, Matrix takes it a step further; in the same section, the specifications states that the data is split between message events and state events (Matrix.org 2018, "Room structure"). While Matrix adopts the same status distribution, the protocol makes it easier to share those status updates by splitting them into two categories: one for anything relating to messages (eg. new messages, attachments, etc.), and one for the state of the room (eg. who's online/offline, who's typing, etc.).

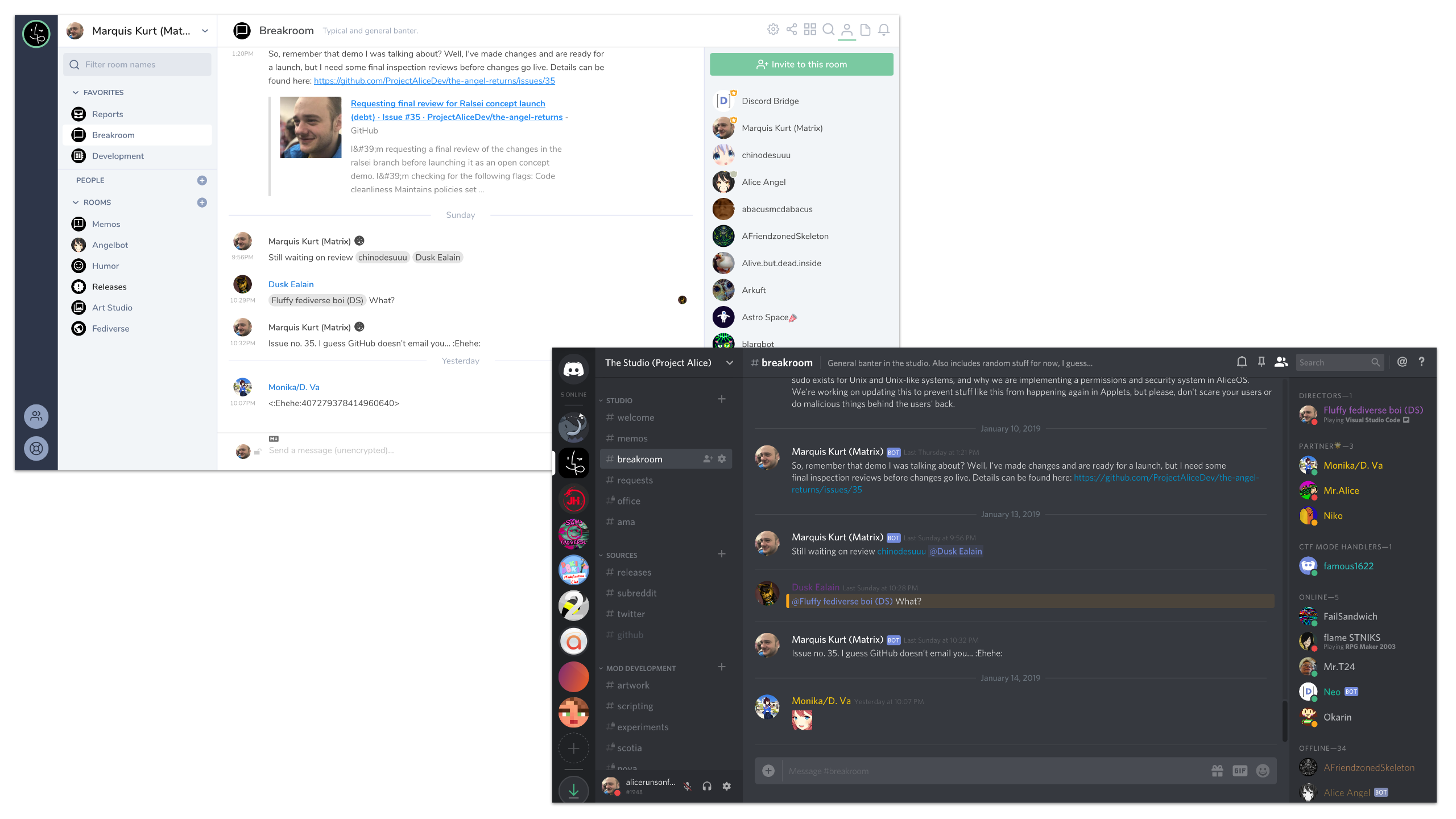

Most importantly, Matrix makes use of Web services to submit data when computers don't have a direct connection. Most particularly, Matrix's Web services, often called bridges, are able to translate messages between services as previously described. Imagine that Alice is using the gaming chat app Discord and Bob is using Telegram, another instant messenger. Alice and Bob have set up a Matrix room to talk to each other more fluidly, but have added two bridges that translate Discord messages and Telegram messages. Because of the way Matrix translates and sends the data, Alice's Discord messages appear in Bob's Telegram chat, and vice versa. Even if Alice and Bob aren't using Matrix natively, they are still able to communicate with each other thanks to the interoperability of those bridges.

Project Alice uses a Discord bridge to connect their Matrix channels and Discord together to let anyone communicate easily.

How is France using Matrix?

See also: Matrix in the French State

In the FOSSDEM 2019 conference, Matthew Hodgson, one of Matrix's developers, discusses what Matrix is and how France is implementing it into their government (Hodgson 2019).

The Matrix protocol, since creation, has received a steady user base, and a few companies have adopted the protocol for their own messaging. Recently, in 2018, DINSIC, the part of the French government responsible for maintaining digital aspects, announced that the government would begin adopting Matrix across departments. In their memo from May 2018, they state that they chose Matrix (albeit a translation) because companies such as Thalès have been using it and that Matrix offers interoperability in an open-source package that DINSIC can contribute to (Wadoux, para. 5). As of April 2019, DINSIC released their frontend, Tchat, to government users with their own contributions. Jon Fingas from Engadget sums up these additions in the opening to his article about this release: "All private conversations are encrypted end-to-end, antivirus software screens all attachments and [...] is stored in France" (para. 1). The antivirus checker is now a part of Matrix's code repositories and end-to-end encryption has been improved significantly.

Although DINSIC has stated that Matrix's usage, as of right now, is limited to government departments, it does raise a potential future where everyone in the French public could use Matrix and Tchat; moreover, this hypothetical expansion could also increase communication activity between the French government and its people. In a study conducted by The University of Pretoria (South Africa) in Buffalo City, T. Hobololo and T. Mawela analyzed public participation with the municipality and concluded that using mobile phones and texting increased participation. Notably, citizens involved in the study stated that the government would have to address the needs of the people and focus on efficiency and effectiveness when using an instant messaging service (Hobololo and Mawela, 65). Continuing from the aforementioned hypothetical situation, the French government would use Matrix to meet these needs.

See also: L’État adopte sa propre messagerie instantanée sécurisée

The Matrix Foundation has made DINSIC's press release about Matrix in France, titled "L’État adopte sa propre messagerie instantanée sécurisée", available for everyone to read (Wadoux).

Matrix's future boosted

France's adoption of Matrix also sets the stage for Matrix's role in the future as a global messaging protocol. In the memo from DINSIC, the ministry stated that they used WhatsApp and Telegram before announcing the switch to Matrix (Wadoux 2018, para. 2). Both WhatsApp and Telegram come with privacy features, but the companies that run them, namely Facebook and Telegram, have ethically questionable practices in terms of privacy and security. While Matrix adoption in France triumphs another "victory" for open-source software, it also sends a message to companies with messaging services: Matrix should be the protocol for transmitting messages because of its interoperability and privacy-focused features, such as decentralization and end-to-end encryption.

Companies such as Facebook, Apple, Google, and Microsoft have the capabilities to create their own messaging services that take advantage of Matrix, though it is unlikely this will occur because of current business practices the tech companies follow. For instance, Facebook might not pursue creating a Matrix-based version of Messenger because Matrix's goals may interfere with the company's agenda, which appears to focus more social engagement and advertising. If Facebook wanted to add an advertisement module to Matrix, they'd have to write an update to the overall specification and propose it back upstream which might get rejected outright because none of the parties that use Matrix would want advertising in their messages; to counter this, Facebook would most likely create their own version of Matrix with said module, changing the protocol and potentially break compatibility with other Matrix servers.

Matrix will inevitably become a primary protocol for messaging because of its quick adoption in France and the protocol’s technical capabilities such as bridging. Although it is unlikely that it will take off quickly and outright replace all existing services, Matrix's bridging abilities will be able to help provide the transition period the world needs to migrate over to a completely different model of messaging. In a way, Matrix is helping us return to the roots of the internet: free, open, and decentralized. In "The Essence of the Internet,” Johnny Ryan describes that the internet works as a network because of social reasons: "researchers preferred the idea of a dumb network controlled by a community of computers using a common protocol [... the] decentralized network prioritized survivability over other considerations" (Ryan 39). Given that the internet's creators intended for the network to be decentralized and open to all, Matrix helps to provide a route back to realizing that potential.

Sources

“France Launches Government Chat App after Fixing Last-Minute Flaw.” n.d. Engadget. Accessed May 1, 2019. https://www.engadget.com/2019/04/21/france-tchap-government-messaging-app/.

Hao Zhang, Zhongkui Sun, He Li, and Jianmin Li. 2015. “A Distributed Instant Messaging System Model.” Metallurgical & Mining Industry, no. 6 (June): 487–94.

Hodgson, Matthew. 2019. “Matrix in the French State.” presented at the FOSSDEM, ULB Solbosch Campus, February 2. https://fosdem.org/2019/schedule/event/matrix_french_state/.

Hobololo, T. S., and T. Mawela. 2017. “Exploring the Use of Mobile Phones for Public Participation in the Buffalo City Metropolitan Municipality.” Agris On-Line Papers in Economics & Informatics 9 (1): 57–68.

“Matrix Specification.” n.d. Accessed March 2, 2019. https://matrix.org/docs/spec/.

Ryan, Johnny. 2013. A History of the Internet and the Digital Future. Reprint edition. London: Reaktion Books.

Wadoux, Rachel. 2018. “L’État adopte sa propre messagerie instantanée sécurisée,” April 20, 2018. https://matrix.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/CP_messagerie_instantanee_Etat.pdf.